Page Updated:- Sunday, 07 March, 2021. |

|||||

Published in the South Kent Gazette, 4 June, 1980. A PERAMBULATION OF THE TOWN, PORT AND FORTRESS. PART 84.

EASTERN HARBOUR Dover harbour underwent a great change during the Roman period. There was a clear tidal estuary at their first coming, but when they left, a delta had been formed, with its outward face in line with the coast, and its inward point extending towards the present site of the Maison Dieu, dividing the river into the east and west brooks. Camden, quoting Geoffrey of Monmouth, states that the filling up of the estuary of the Dour was wilfully done by a British Tributary King, Arviragus, circa AD 70, to keep the Roman ships out. Twentieth century writers on archaeology have doubted this but local experience makes it easy to -understand that an attempt to do this, which might have failed at the time, would have unforeseen results later. A small artificial obstruction would have hastened the joint agency of the sea and the river — the sea shelving up the shingle into the river’s mouth, and the earth washed down the stream against the shingle bank would have formed a delta. These natural causes operating during the five centuries of the Roman occupation, so stemmed the river as to divide it into two streams, one running west and the other east. The eastern stream had the most direct course to the sea, and where it emptied, near the Castle, was formed the Eastern Harbour. It was during the early days of this Eastern Harbour that, it is said, a wall was built by King Withred, across the seaward face of the delta, to protect his newly-established canons at St. Martin-le-Grand from sea robbers. This harbour was approached through East Gate, which stood about 75 yards east of the site on which the old church of St. James’s was subsequently built. There, under the town and Castle walls, the harbour remained for more than a thousand years. That thousand years covered a varied and picturesque stretch of Dover history. It began with the departure of the Romans, continued during the bloody rivalries of the Saxons and Danes, saw the coming of the Normans, witnessing both the rise of the Cinque Ports Confederacy to the zenith of its power and its decline, as well as the beginnings of the cross-Channel traffic, which has been growing ever since. Since the first edition of this book appeared the continued excavations made at Roman Richborough have induced various writers on Roman Britain to assert that Richborough (the Rutupiae where there was a big military station) was the Roman port for the Continent. On the scantiest of evidence it was suggested that Richborough was the chief landing place for Roman troops in the time of Agricola. Tacitus the historian and relative of Agricola does not support such a theory. His description of the return of Agricola speakes of “his passage in the narrow straits.“ As regards the landing of an army, it seems to be forgotten that large transports were not available in those days but a multitude of small galleys would have been utilised, landing on a broad expanse of beach. It appears certain that the Rutupine shore was the name given to this coast from Dover to Thanet and to select one small part of the coast as the port used by the naval transport for the Roman legions ignores consideration of space.

PASSAGE MONOPOLY It was from the snug little harbour under the Castle, commanded by bowshot from the fortress walls, that the passage from England to Prance was organised, by royal charter, as a monopoly for Dover, in the year 1227. Owing to the existence of that monopoly, the traffic across the Straits, from Dover to Wissant, was so great that, in 1312 and in 1323, agreements were made to regulate it, compelling the fellowship of Dover mariners who worked the passage, to make fair charges and to take their regular turns. In the year 1343, a royal ordinance compelled the fellowship to pay a certain proportion of their profits into a common chest of the Corporation, to be used for the upkeep of the harbour.

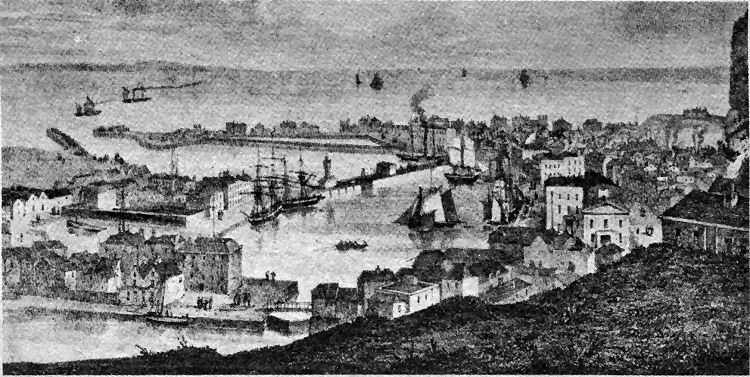

An attractive engraving of a view across the tidal harbour to the Crosswall and Granville Dock. It is not dated but the presence of towers on either side of the Crosswall entrance to the dock puts the date between 1830 when they were erected and about 1871 when they were demolished as part of the improvement carried out at the Granville Dock to cater for the new steamers and sailing ships with a deeper draught. The tower on the western side was a compass tower with a compass on the faces instead of a clock as in the tower of identical design on the eastern side. The clock from this tower was transferred in 1877 to a new clocktower near the Prince of Wales Pier.

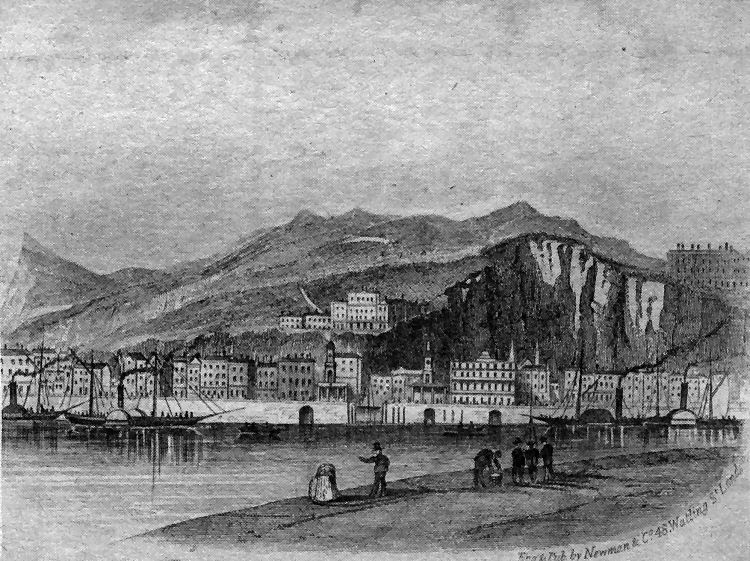

The picture, above, is from an engraving said to date from 1838, but it shows the compass tower only partially completed, suggesting the original drawing was of an earlier date. To the left are the North and South Piers and near what is now Lord Warden Square is an enclosed stretch of water which was Hilled via a link with the Crosswall and used to flush out the shingle bar which regularly choked up the harbour entrance before the Admiralty Pier was built.

|

|||||

|

If anyone should have any a better picture than any on this page, or think I should add one they have, please email me at the following address:-

|

|||||

| LAST PAGE |

|

MENU PAGE |

|

NEXT PAGE | |