Page Updated:- Sunday, 07 March, 2021. |

|||||

Published in the South Kent Gazette, 13 June, 1979. A PERAMBULATION OF THE TOWN, PORT AND FORTRESS. PART 11.

ST. PETER’S CHURCH. About a century or more after the Norman Conquest, there came into existence, on the north side of the Market Square, as old Dover deeds describe it, “The Church and Cemetery of the Blessed Peter of Dover.“ There is no description or drawing left to indicate what St. Peter’s Church was like, but a few samples of its sculptured stones were found in clearing the site for Lloyds Bank, and they point to its origin being the close of the 11th century. There are only three references to this church, as far as we know, in the Dover Corporation deeds. In one, dated 26th April, 1342, occurs the reference:- "The Cemetery of the church of the Blessed Peter of Dover“; in another, dated 1392, “The parish church of St. Peter, Dover“; and in another, dated 1416, “The Church of St. Peter in Dover.“ This church, from 1367 until 1581, was used as the place where Members of Parliament and the Mayors of Dover were elected, and from its tower the curfew bell was rung. In the year 1581 the church appears to have so fallen into ruin that it could not be used, and St. Mary’s, in its stead, became the parish church. Queen Elizabeth, some time prior to the year 1584, made a grant of the church to the Mayor and Jurats to be sold to raise money to repair the harbour. An accusation was made, in 1584, against Thomas Allen (formerly Mayor), of not having accounted for the money derived from the sale of the property of St. Peter’s Church, and, in consequence, he secretly left the town and was never seen again! A great many of the leading men of Dover were buried in the chancel of St. Peter’s, the latest recorded being in the year 1572.

A HEAD WITH A HISTORY. When excavations were being made in tile year 1810, another interesting feature was revealed — a chalk receptacle containing a human head, evidently severed from the body by beheading. That is supposed to be the head of William de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk, who was banished from the realm in the year 1450. Suffolk had fallen into disgrace owing to his mismanagement of the war in France, and being impeached, was sentenced to banishment. The people were so enraged at this leniency that they intercepted the Duke’s ship when passing through the Straits of Dover, and beheaded him. An ancient chronicle, which fell into the hands of the historian Speed, gives the following version of the affair:— “The King, seeing that all this land hated the Duke deadly, and that he must not here abide the malice of the people, exiled him for a term of five years. And the Friday of the 2nd day of May, 1450, he took his ship at Ipswich and sailed forth into the high sea, where another ship, called the Nicholas of the Tower, lay wait for him and took him. And they that were on board granted him the space of a day and a night to shrive himself, and make himself ready to God. And then a knave of Ireland smote off his head on the side of the boat, and the body with the head was cast to the land at Dover.“ Such is the story of the head which was found in the hollow chalk receptacle in the vaults under St. Peter's Church. When the later excavations were made near the same site for widening Cannon Street in 1892-93, other chalk coffins were found. One of them, which contained the remains of a man, a woman, and a child, was placed in the Dover Museum.

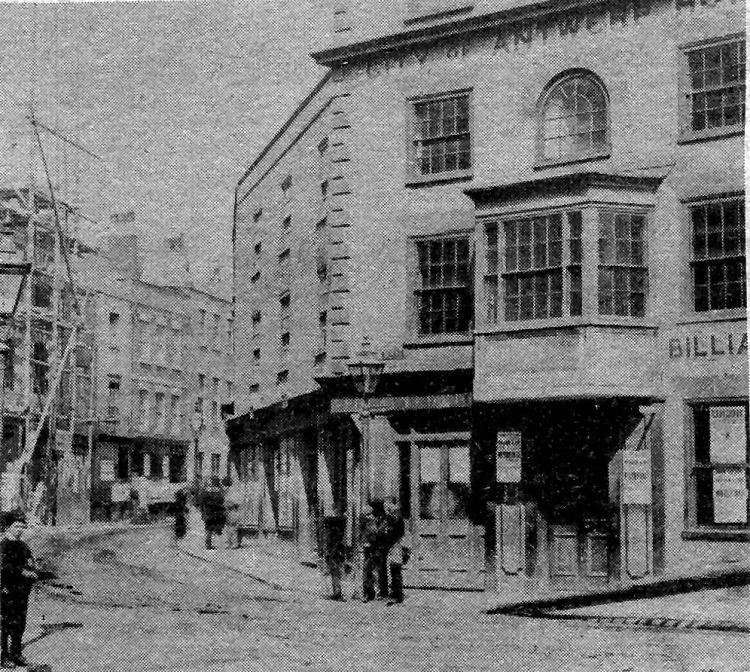

NORTH SIDE — LATER HISTORY. Although regular services at St. Peter’s Church seem to have ceased in 1581 there was a vicar appointed as late as 1611 which suggests that the building had not entirely disappeared at that time. The internal construction of the old houses or mansion subsequently built on the church site, but which have now disappeared, like the church, pointed to an age of about three centuries. The basements, except where they had been raised, were considerably below the surface of the Market Place, the result of the raising of the ground by road mending since the beginning of the Stuart Period. It is very probable that, until 1905, not one of the houses had been wholly rebuilt since the line of frontage was first erected on the site of the church and churchyard which had occupied the whole of that side of the square. In the last century there were seven tenements, but, judging from the way the apartments overlapped each other, it looked as though the whole range had been one large mansion. The oak beams were massive, and in some of the rooms there were traces of fireplaces and other work of the Jacobean period, indicating apartments fit for a man of wealth and position. The walls, too, in several instances were of stone rubble, very thick, and below ground the foundation walls of the church were still there when the foundations of the Lloyds Bank were dug. The "Antwerp Hotel," at the Cannon Street comer, was much used by the old Dover Corporation as a place where they refreshed themselves and did business, and the Court of Lodemanage was held there at the time of the Duke of Wellington’s Wardenship. These tenements having all, as far as in known, been devoted to trade or domestic purposes, nothing of note is left on record respecting them, except the interesting fact that on the steps of Igglesden’s original shop David Copperfield was represented as sitting to rest when weary with searching for his aunt, Betsey Trotwood. Those steps, and the old frontage disappeared in the transformation of “Igglesden’s Corner.“ The entire aspect of the northern side of the Square was changed by the building of Lloyds Bank in 1905. In removing the old buildings there was found in a heap a large quantity of human bones, supposed to have been collected from tombs in St. Peter’s Church, and they were re-buried, with an appropriate religious service, on the western side of St. Martin’s Churchyard.

The old City of Antwerp Hotel, on the north side of the Market Square, which was demolished as part of the Cannon Street widening scheme in the late 1890s.

EAST SIDE HISTORY. Historians have left very little on record concerning the eastern side of the Square. When the Saxons were church-building on the western side, this particular part was under water. It was here that the ships are said to have cast anchor in the days of King Aviragus, and for centuries afterwards the tidal Dour formed the eastern boundary of the area, so that it would not be reasonable to expect to find on this side of the Square traces of any structures which would vie in antiquity with those on the west. But although there are no ancient foundations, there are curious facts which act as useful pointers to the past. It is a singular circumstance that while the whole of the other part of the Market Place and its vicinity is in St. Mary’s, the building, part of which is a wine merchant’s, on the southern side of Dolphin Lane is in the parish of St. James’s. It seems to be generally recognised that the river is the boundary between the two old town parishes, and yet here we find a small promontory of the St. James’s territory projecting itself over the river right into the Square. Why? The obvious conclusion is that the river, which formed the ancient boundary, in early days ran into the Square, but having now fallen into the rear, has left this property on the opposite bank isolated from the rest of St. James’s parish.

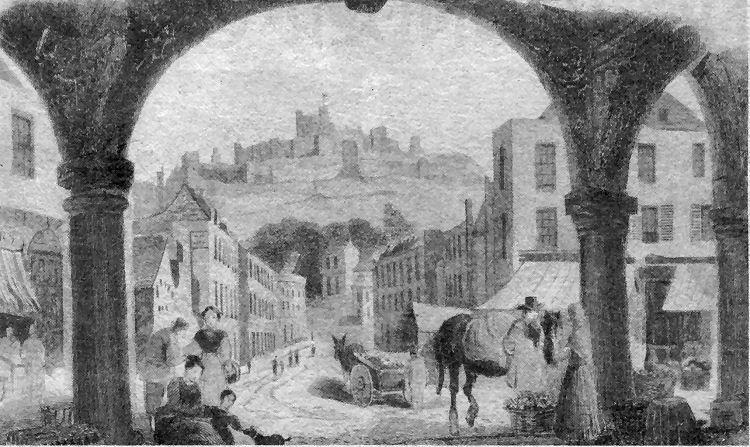

A charming old print of Castle Street and the Castle, viewed from between the pillars of the old Guildhall, in the Market Square, on market day. Particularly interesting is the shop at the corner on the left which bears the name Saunders and not Igglesden, a long established business which is usually pictured there. Still standing, but with a new frontage, the building subsequently became a bookshop and stationers.

|

|||||

|

If anyone should have any a better picture than any on this page, or think I should add one they have, please email me at the following address:-

|

|||||

| LAST PAGE |

|

MENU PAGE |

|

NEXT PAGE | |