|

From the

https://www.msn.com 26 January 2026, by Akhtar Makoii.

The pub that survived disaster, but not Rachel Reeves.

Pubs are ‘the only place in the world where you can say what you

like,’ says Bob Griffiths, 82, licensee of The Phoenix.

Bob Griffiths unlocks the door of The Phoenix at noon on Saturday,

the last day a pub will ever open on this corner.

His hands move with practised efficiency, turning the key, flipping

the sign, lighting the fire in the white building’s chimney.

He cleaned the draught lines this morning for the final time, a

ritual performed thousands of times over 15 years, today rendered

ceremonial.

The Telegraph spent the night before with locals dancing until

midnight, their dogs weaving between ankles, the music loud enough

to shake memories loose from the walls.

The Phoenix, in Canterbury, Kent, has been one of those places that

holds more than just memories.

A pub on the corner of Cossington Road and Old Dover Road where

strangers became friends, where first dates turned into proposals,

where cricket victories were celebrated, and defeats were drowned.

Where people have gathered for 152 years to be less alone.

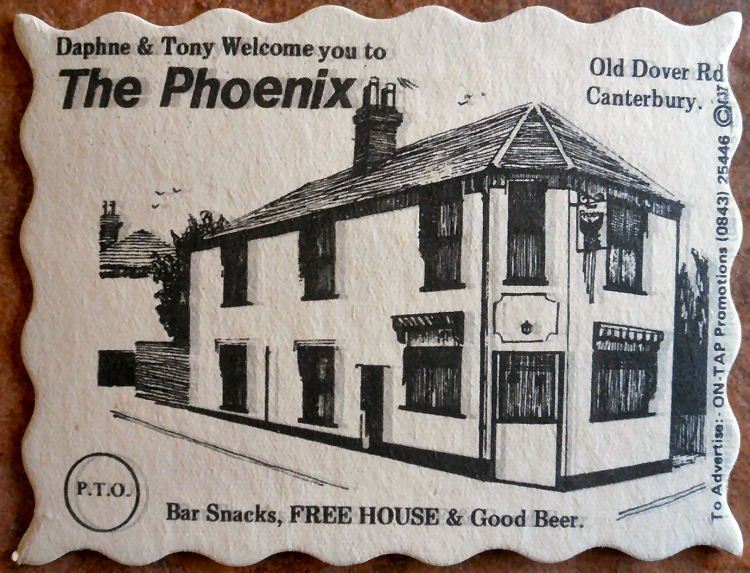

Renamed The Phoenix after a fire gutted the Bridge House Tavern in

1968, there has been a pub on this Canterbury corner for 152 years -

Ben Montgomery

But it has also been the place where hearts broke quietly over pints

that grew warm.

Now, in the pale January light, farewell letters sit stacked on the

bar. Bob picks one up, then another, reading words that might

explain what he cannot quite grasp himself.

The Phoenix rose from ashes once before. In 1968, fire gutted the

Bridge House Tavern that had stood here since 1874.

Someone decided its new name should honour resurrection. But 58

years later, rising costs and taxes, and Chancellor Rachel Reeves’s

failure to support the sector have proved too much.

“Everything is changed, we are losing our democracy very quickly,”

Bob, 82, says, his voice carrying the weight of something larger

than beer and closing time.

“I don’t quite understand what is going on to be honest. This is the

only place in the world where you can say what you like, in this

very place, in pubs. They’re all shutting down.”

He remembers childhood in Chatham, where his father served in the

Royal Navy.

“When I was a kid, there were 24 pubs in Brook Street in Chatham; 24

pubs. Three next door to one another.”

Sharon Higenbottam, 67, sits near the window with the weight of

symmetry pressing on her. She first walked through these doors as a

15-year-old in the 1970s, stopping for a Diet Coke with a friend on

their way to a Simon Langton Girls’ School disco.

No alcohol, just two teenagers seeking refuge before a night of

awkward dancing.

“It’s such a happy place,” she says, her voice catching on the

present tense. “I feel safe walking here if I’m on my own.”

“People feel lost,” she says simply. “Bob and Nilla, they’ve been

here for I don’t know how long, but they’re always very welcoming.”

Sharon Higenbottam, 67, has been coming to The Phoenix since she was

a teenager.

The doors lock. And Sharon will have to find somewhere else,

somewhere farther away, somewhere that doesn’t feel as safe for a

67-year-old woman walking alone on a Friday night.

“Canterbury is losing so many pubs,” she says. “It’s a sad day for

Canterbury, actually.”

Bill Wilkie, 80, can recall with precision the day he had his first

drink at The Phoenix: Jan 1 1970. He’d just returned from Germany

and started work down the road.

At lunchtime, he and his new colleagues walked up to the pub. He’s

been coming ever since, on and off. Mainly on.

“Very sad,” Mr Wilkie says. “The prospect of walking past it when

it’s going to be dark and dead, it’s horrible.”

Mr Wilkie spent his career as a surveyor and estate agent in

Canterbury. He’s watched the pattern repeat across Kent’s villages:

pub closes, social life dies.

“I’ve seen particularly in the villages where the pub closes down,

they’ve got no social life at all really, got no sense for their

activities.”

“It’s not the smartest of pubs as you might see,” Mr Wilkie

acknowledges, “but there’s a lot of us who live here locally so this

is like our social centre, focus, and that’s under threat.”

His most vivid memory of The Phoenix is standing outside, watching

the Tour de France ride past when it came to England several years

ago. The rest, he says, “just blurs into a series of nights of

drinking”.

Bill Wilkie, 80, has watched the pattern of pub closures repeat

across Kent’s villages.

Spencer Griffiths, Bob’s son, stands near the bar with the

arithmetic of failure written in his posture.

“It is both because of affordability and their physical health that

they are closing it down,” Spencer says.

He adds: “The affordability is huge. For instance, if they wanted to

retire and get somebody else the lease, they could get someone else

to run it if it was profitable, but it is not. It is absolutely

correct that there are no profit margins.”

He ticks off the pressures like a coroner listing causes of death:

business rates, the energy crisis that sent bills spiralling before

this government and under it. The physics of bodies wearing out. The

economics of an industry collapsing.

Bob, however, resists the easy political blame. Where others point

fingers at Westminster, he points at something else.

“People have stopped drinking,” he says. “And I don’t quite

understand why people stop drinking, but there you go.”

His regulars disagree. Vehemently.

A man who has drunk at The Phoenix for 40 years has a different

account.

“The main reason is to blame Labour because they could not reduce

the prices,” he says. “Previously, I would be able to drink all

night for £20, now it won’t buy one round for three friends.

“The Labour Party and their policies are to be blamed to some extent

because they have not been able to control inflation and that has a

huge impact on the local economy because people cannot afford it.”

Some blame the Government. Some blame culture. Some blame both. All

agree that something essential is dying.

David Foley, who is in his 70s, remembers his first pint here in

1972. He speaks with the practised irony of someone who has wrestled

the world’s problems over beer and found them unsolvable.

“It is fair to say hospitality in east Kent is under severe pressure

for a variety of reasons, which include rates and taxation,” he

says. “The Phoenix has risen from the ashes once before.

“In the last two weeks here, we have resolved the problem of global

warming, we have resolved the problem of Gaza.”

He pauses for effect.

“We are about to turn our attention to something more serious, such

as the Kent cricket team, which is at the bottom of division two,

but before the season starts in April, we won’t have the opportunity

to do so. Kent cricket would also suffer.”

David Foley, a Phoenix regular since 1972, says that hospitality in

east Kent is under severe pressure.

Pubs are under financial strain because of the Labour Government’s

increases in business rates, National Insurance employer

contributions and the minimum wage, which have coincided with the

end of pandemic-era VAT relief.

Andrew Heywood lives 40yds up the road. He moved to the area in 2003

and has been coming to The Phoenix ever since.

When Mr Heywood worked in London and commuted by bicycle, he’d

arrive back at Canterbury station at nine or 10 at night, exhausted

and starving.

He’d stop at The Phoenix, and Bob would see him walk through the

door and have a plate of sandwiches waiting on the bar. “That’s the

way he treated you,” Mr Heywood says.

“I feel quite emotional about it, actually,” the 67-year-old

chartered surveyor admits. “I don’t know, where will I go? Where’s

the community hub around here? There isn’t one any more.”

The Phoenix has become the foundation of his social life. The same

group gathers for Friday music nights, then the friendships spill

beyond the pub’s walls – dinner parties, gatherings, a whole social

network built on the foundation of a neighbourhood bar.

“I’ve met so many friends here. This whole group of us on a Friday

night come down, and as a result, we go around to each other’s

houses and have parties and things like that, because we met in the

pub.”

The Phoenix hosted Friday music nights where people danced,

Wednesday quiz nights where they competed, and countless ordinary

Tuesdays where they simply existed in the same space.

Andrew Heywood, 67, says the neighbourhood will lose its community

hub when The Phoenix closes.

Bob talks about democracy and free speech, about the pub as the last

place you can say what you like.

The irony isn’t lost – in a country that prides itself on free

expression, the spaces where that expression happens are vanishing

faster than anyone can count them.

The fire in the chimney burns, warming the white building one last

time. Bob has neuropathy in his feet and diabetes becoming

problematic.

He and his wife Nilla have earned rest. The lease is up. The numbers

don’t work. The people have stopped coming in numbers that pay the

bills.

If the lease wasn’t up, would he like to continue running it? “No,

not really,” Bob admits. His body has made the decision, economics

only confirmed it.

Around the pub, objects wait for removal. A cricket picture that

cost £240 will go home with Bob, though he doesn’t follow cricket. A

decade and a half of accumulated life needs packing, transporting,

finding new places. Memory has weight and takes up space.

The Phoenix rose from fire in 1968. But on Sunday, the locks will

change and The Phoenix that rose from ashes will stay buried.

|