Page Updated:- Sunday, 07 March, 2021. |

|||||

Published in the South Kent Gazette, 16 May 1979. A PERAMBULATION OF THE TOWN, PORT AND FORTRESS. PART 7.

The obvious reason why building in the Market Place had not been carried out before the Reformation was that whilst St. Martin’s Priory existed, the Corporation, although by user they might hold a market on the open space, were not at liberty to build on that area; and even after the Corporation had taken possession, and built their Court Hall, in 1605, they found that they had no right to the land, nor yet to the Court House which they had built thereon. They were, in fact, trespassers, the whole area being the lawful property of James Hugessen, merchant adventurer, of Dover. How he became possessed of it is not very clear, but it is sufficient for our purpose to know that Thomas Attwell, the Corporation’s attorney, admitted the fact. Happily, James Hugessen was a reasonable man; all he wanted was an admission of his right (which acknowledgement would doubtless improve his title, which was none too strong, to surrounding property), and then he was prepared to act as the noble benefactor, and make over, by a deed of gift, the whole Market Place, with the Court Hall and other buildings extending as far as an old almshouse at the corner of Market Lane and Queen Street. The Corporation admitted the Hugessen claim in the amplest terms possible, and the deed of gift was executed, giving the town possession for ever. In examining the surrounding buildings, the west side of the Market Square, by the claim of antiquity, invites our first attention. Nine successive sets of builders have toiled on that spot—ancient Britons, the Romans, the Saxons, Normans, mediaeval restorers, the grabbers of Church property in the 16th century and the re-builders of the 18th century, 19th century and the 20th century.

ROMAN BUILDINGS. The Romans in Dover probably did not build high, but, having unrestricted area, they covered much ground. Foundations of their baths were found, in 1778-79, by Lyon, under the western end of St. Mary’s Church. Traces of them were found again at the restoration of St. Mary’s, in 1843, and they were met with again in May 1881, under the Carlton Club, which stood near the comer of the Market Square and Market Street. Commenting on the 1881 discoveries Canon J. Puckle, Vicar of St. Mary’s, said: “The traces of Roman work were many and curious; large portions of side retaining walls in beautifully laid courses of boulder flints, chambers and hypocausts, and everywhere the same concrete floor as in the remains at St. Mary’s.“ Then, in the 1970s, Kent’s Archaeological Rescue Corps, excavating off Market Street uncovered the remains of a military bath-house complex at least 60ft. long with walls still standing up to 13ft. high. It was dated as about the 3rd century A.D. There were at least five rooms, all centrally heated, with walls plastered and painted red and floors of hard pink mortar. Among the rubble filling the site was a quantity of Roman tiles stamped “CLBR,“ the abbreviation for the Roman fleet, Classis Britannica. The bath-house is opposite the site of the Roman “Painted House“ which the archaeologists unearthed on the north side of Market Street in 1971 and which they have preserved for posterity inside a protective building they put up themselves. This is open to the public. A damaged, coarse oolite statue, 4ft. high, of a woman was discovered during the excavation for the Carlton Club, amidst the ruins of the Roman building found below ground. (The Architect of the Carlton Club, Mr. E. W. Fry, told the Kent Archaeological Association that he thought they were the remains of a Roman Forum.) The statue was broken and in three pieces; after being repaired, it was placed in Dover Museum. Its origin has given rise to much speculation.

SAXON WORKS. Proceeding to Saxton times archaeologists searched in vain, until the 1970s, for traces of the church built by King Withred for the College of Canons which he removed from the Castle in 696. The Rev. Dr. F. C. Plumtre, who, in 1845, made careful observation of the ruins of St. Martin-le-Grand, then standing among and in the rear of property on the western side of the Market Square, said there was no reason to doubt that the ruins were those of the ancient church of the Monastery; but he found no actual Saxon remains. During excavations for the old National Provincial Bank at the Cannon Street corner of the Market Square, in 1956, evidence was found of a big fire which at one time swept through a building on the site. This was thought to have been soon after the Norman Conquest. Another discovery was of a tomb constructed of chalk blocks, containing a skeleton. At first it was thought to be that of an important Saxon chief but it was finally concluded that it was more likely Norman. In 1978 archaeologists made what was heralded as the most important discovery since the “Painted House“ was found. They uncovered the remains of a Saxon timber building thought to be the original church of St. Martin-le-Grand built by Withred. Finds made on the site suggested the building, 65ft. long by 30ft. wide dated from between the 7th and 9th centuries. Other finds made the same year suggested occupation of the area as early as 2,000 years B.C.

NORMAN CHURCH. The last visible remains of the massive Norman church of St. Martin-le-Grand were removed in 1955 prior to building new bank premises near the Market Street comer of the Market Square. Until that year there was still visible, towering some 30ft. or so above pavement level, a mass of masonry which had stood there for something like 800 years. The relic was for a long time hidden by a succession of buildings which were erected on the site. One builder after another seems to have been reluctant to destroy it and renewed public interest in the church was created when war damage to adjoining property brought the remnants back into the public eye in the 1940s. Together with a smaller portion of monastery wall to the rear, incorporating an archway, it was demolished in 1955 but some of the stone was incorporated as a feature of the new bank. Inside the bank a showcase was set up to display relics found on the site, including a piece of the jawbone and teeth of a mammoth. Notes made in 1845 by Dr. Plumpre, Master of University College, Oxford, who was a keen archaeologist, tell us a great deal about the state of the church at that time. Helping to complete a picture of what the Norman building looked like is a ground plan, made the same year, of the eastern end of the church, and various prints which have been published over the years showing the ruins as they appeared at earlier periods.

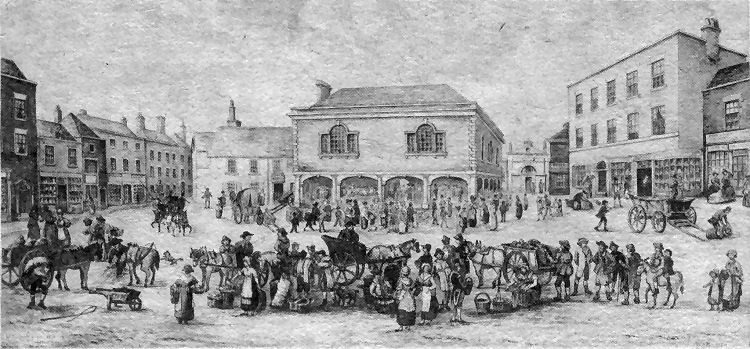

A BUSY Dover market place scene based in a J. E. Youden sketch dated 1822. A painting based on this hangs in Dover’s council chamber. Interesting features include the old "Fountain Inn," to the left of the Guildhall, with a padlock emblem on the wall, the old prison to the right next to the premises of a baker and hairdresser, Morphew’s tea and tallow chandlers’ shop and Durtnall’s ironmongery business.

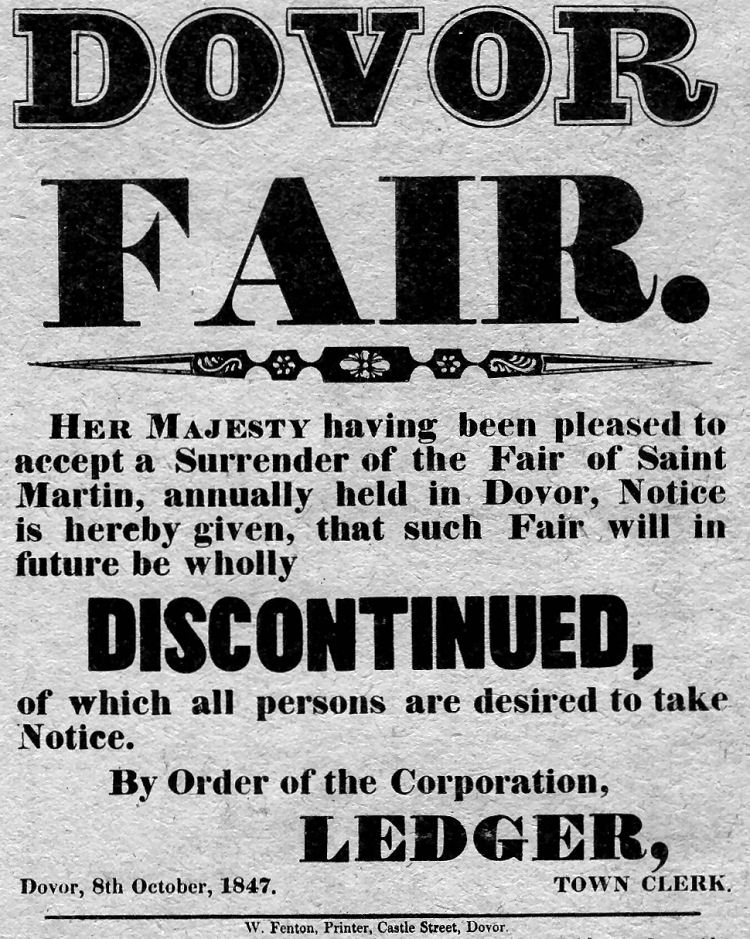

A poster announcing the 1847 order by Dover Corporation ' closing down the annual “ Dovor Fair “ of St. Martin which was held in the Market Square.

|

|||||

|

If anyone should have any a better picture than any on this page, or think I should add one they have, please email me at the following address:-

|

|||||

| LAST PAGE |

|

MENU PAGE |

|

NEXT PAGE | |